Contours of a Port City

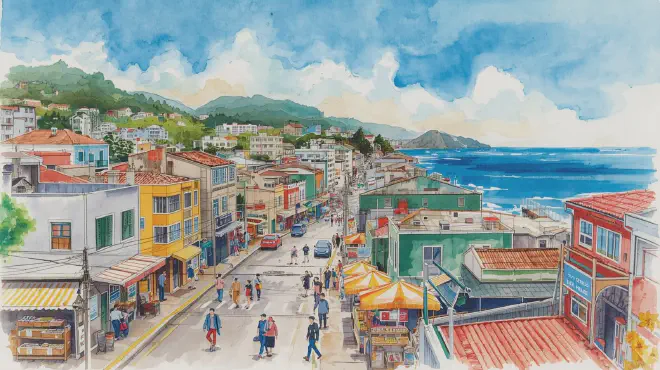

Busan is South Korea’s second-largest city, yet it possesses a character entirely distinct from Seoul. Situated at the southeastern tip of the Korean Peninsula, this port city faces Japan across the Korea Strait and has long flourished as a maritime gateway. A temperate climate, undulating terrain, and the unique landscape where ocean and mountains meet as neighbors—from the modern high-rise coastline of Haeundae to the colorful houses blanketing the slopes of Gamcheon Culture Village, this city breathes with old and new intricately intertwined.

People visit Busan for many reasons: seafood cuisine, hot springs, film festivals, or the harbor views. I chose this city for no particular purpose. I simply wanted to walk through a seaside town. To climb the slopes until breathless, immerse myself in the clamor of markets, and dine alone in an evening restaurant where unfamiliar words fill the air. With only such vague desires in my heart, I descended upon Gimhae International Airport.

Day 1: Led by the Scent of the Tide

From the window of the light rail connecting Gimhae Airport to downtown Busan, the city’s outline gradually reveals itself. After passing through low hills, clusters of dense buildings appear, and in the distance, the blue of the sea glimmers. I transferred to the subway at Seomyeon Station and headed to Nampo-dong, where I’d booked accommodation. The subway car was filled with the gentle atmosphere of afternoon—students’ laughter and the quiet presence of people gazing at smartphones felt comfortable.

The guesthouse in Nampo-dong was small. After leaving my luggage in the narrow but clean room, I immediately went outside. On the first day of travel, when the body hasn’t yet adjusted to the journey’s rhythm, is the best time to walk the streets. Following a map toward Yongdusan Park, I observed the small shops lining the alleys. Cosmetics stores, food stalls, cafes, and old shops with signs mixing Hangeul and Chinese characters. Busan’s everyday life overlapped with its tourist facade.

As I began climbing the slope to Yongdusan Park, the city’s noise gradually receded. Busan Tower, standing atop the park, is known as this city’s landmark. From the observation deck, the entire panorama of Busan Port spread before my eyes. Countless containers arranged in neat rows, cranes moving quietly, enormous ships at anchor. There was something there that might be called the functional beauty of a port city. Shifting my gaze right revealed the greenery of Yeongdo Island; to the left, the high-rise buildings toward Haeundae. And before me, Busan Harbor Bridge straddled the sea.

Descending from the observation deck, dusk was already approaching. Feeling hungry, I headed toward Gukje Market. Even before entering the market, the savory smell of grilled fish and the fermented scent of kimchi drifted toward me. On both sides of the passageways, shops selling clothing, dried goods, sundries, and food ingredients crowded together. Every shop brimmed with vitality, and the vendors’ calls rang out in Korean and occasional Japanese. I walked through that fervor without buying anything.

Beyond the market lay Jagalchi Market, Busan’s representative seafood market. On the first floor, live seafood sits in tanks, and on the second floor, restaurants cook them for you. Flounder, sole, abalone, sea cucumber, sea urchin. Watching the creatures moving in the tanks, I chose a restaurant at random. The ajumma working there cheerfully showed me to a seat and recommended the flounder sashimi I’d pointed at. Words didn’t connect, but gestures were sufficient.

The sashimi brought to me was more plentiful than expected. Translucent white flesh, thinly sliced and arranged on a plate. I wrapped it in lettuce with garlic and sesame oil and brought it to my mouth. The springy texture and subtle sweetness. Alongside the sashimi came maeuntang, a spicy soup made from the flounder’s head. The bright red soup wasn’t as spicy as it looked; the fish stock was thoroughly effective, warming me from the core. I’d worried whether I could finish it alone, but before I knew it, the plate was empty.

When I stepped outside after the meal, night had fully fallen. Nampo-dong’s entertainment district showed a different face than daytime, lit by neon. At BIFF Square, stalls were selling hotteok, a Korean-style filled pancake. Biting into the piping hot hotteok filled with brown sugar and nuts, I slowly traced my way back to the guesthouse. The first night in Busan was filled with the scent of the tide and the people’s vitality.

Day 2: Between Color and Silence

The next morning, I woke early. Light streaming through the window announced the journey’s second day. I decided to have breakfast at a small restaurant near the guesthouse. The menu was only in Hangeul—I had no idea what it said. When I gestured to the server for breakfast, she nodded with a smile and disappeared into the kitchen. Eventually, what arrived was haejangguk, a beef bone soup. The milky-white soup contained beef and green onions, served with rice, kimchi, and small side dishes. Sipping the gentle-tasting soup, I thought about how to spend the day.

I decided to visit Gamcheon Culture Village in the morning. Taking the subway and then transferring to a small bus, I headed up the mountainside. The bus wound up the narrow slope road, and through the window, houses stacked in tiers came into view. Gamcheon Culture Village was originally a settlement where refugees from the Korean War took shelter. Formed in the 1950s, this village was long considered a poor district, but around 2009, it was revitalized through art projects and is now one of Busan’s representative tourist sites.

Getting off the bus, before me stood a lookout point called “Machu Picchu.” The view of the village from there was truly spectacular. Houses painted in pastel colors filled the slope like a blanket. Pink, blue, yellow, green. Each house asserted its individuality while harmonizing as a whole. Murals decorated the alleys, small sculptures dotted the landscape, and the entire village felt like a single art museum.

As I began walking through the village, there were many tourists. Koreans, of course, but also Japanese, Chinese, and Westerners. Everyone explored the labyrinthine alleys with maps in hand. I too let myself flow with the current. A statue modeled after “The Little Prince,” a mural of swimming fish, an art piece repurposing an old well. Each seemed like an attempt to connect the village’s history with its present.

After climbing and descending slopes, I found myself in a quiet alley with fewer tourists. There stood houses where people actually lived, with laundry hanging and a cat sunbathing. I realized that while known as an art village, this was still a living space. In front of one house, an elderly woman sat in a plastic chair sorting beans. When our eyes met, she smiled softly.

By the time I left the village, it was past noon. I boarded the bus again and headed toward Haeundae. Located in eastern Busan, Haeundae is one of Korea’s most famous beaches. When I got off the subway, the deep blue ocean spread before me. There were no bathers at Haeundae in November, but people walked along the beach and sat on benches gazing at the sea.

I too descended to the sand and walked along the water’s edge. The sound of waves washed away all the city’s noise. My feet sinking into the sand, I simply walked. What lies beyond the ocean? Japan? Or somewhere more distant, unknown? The sea gave no answer, only sending waves in and drawing them back.

In the evening, I had a late lunch at the market street in Haeundae. I entered a restaurant serving milmyeon, cold noodles. Busan-style cold noodles have thinner noodles than Pyongyang cold noodles, and the soup is refreshingly light. Cold soup with floating ice and chewy noodles. Simple yet endlessly satisfying. Leaving the restaurant, fishmongers’ ajummas were chattering cheerfully in the market. Listening to their voices, I boarded the subway again.

That night, I visited Seomyeon’s entertainment district. This area bustling with young people was filled with neon and music. But what I headed for was pojangmacha—a tent bar village at the edge of the district. Makeshift stalls covered with vinyl sheeting lined up, each nearly full. Choosing one stall and entering, groups of earlier customers were drinking soju and chatting.

I ordered tteokbokki and sundae. Tteokbokki, the sweet-spicy rice cake stew known even in Japan, was particularly spicy here. Eating the piping hot tteokbokki while sweating. Sundae is a dish of pig intestines stuffed with glass noodles and vegetables, with a distinctive texture. Far from refined, but this simplicity felt perfectly suited to a Busan night. The neighboring group burst into laughter, the proprietor busily cooked, and outside, a cold wind blew. In the warmth of the tent, I felt the second day of my journey drawing to a close.

Day 3: A Morning of Farewells and the Weight of Memory

On the final morning, I woke with a slight sense of reluctance. With time before checkout, I packed my belongings and went out for a last walk. I headed to Taejongdae. A cape jutting from Busan’s southern tip, developed as a natural park. After transferring between subway and bus, I arrived to find ocean, rocks, and forest.

I walked Taejongdae’s trails. Waves crashing against the cliffs were powerful, the sound of water striking stone echoing. From the observation deck, the Korea Strait stretched out. On clear days, Tsushima Island is visible, but on this day, it was too hazy to see that far. Still, standing in this place, I felt viscerally that Busan is a city that has lived alongside the sea.

I sat on a bench near the lighthouse and gazed at the ocean for a while. The journey’s end was approaching. What had I seen, what had I felt in these three days? The market’s vitality, the fatigue of slopes, the sound of the sea, the warmth of meals, the resonance of unfamiliar words. All of it converged in this moment. Perhaps travel is, in the end, an accumulation of such fragments.

Leaving Taejongdae, I returned to the guesthouse. I collected my luggage and checked out. Looking at the clock, there was still time before heading to the airport. I decided to walk through Nampo-dong’s alleys one last time. Roads I’d walked yesterday, shops I’d seen the day before. Three days was too short—I’d only traced the city’s surface. Yet certainly, I had been here.

Before noon, I entered a small restaurant for a light meal. I ordered kimchi jjigae. Steam rising from the bubbling pot, soup where kimchi’s sourness and pork’s umami melted together. Eating it poured over white rice, I thought I would never forget this taste. Taste is engraved in memory’s deepest place. If ever I have kimchi jjigae again, I’ll surely remember this Busan restaurant.

I took the subway to Seomyeon, then boarded the airport-bound light rail. The scenery from the window should have been the same as when I arrived three days ago, yet somehow it looked different. An unknown city had become a slightly known city. Just that, but that was everything.

Waiting for boarding in Gimhae Airport’s lobby, I ruminated on these three days. What had Busan given me? The answer doesn’t come easily. But the ocean’s scent, the slopes’ incline, the market’s clamor, the tent bar’s warmth, and above all, the sound of my own footsteps walking this city—all certainly remain. That was enough.

An Imaginary Journey, Certain Memory

This journey doesn’t actually exist. I never descended upon Gimhae Airport, never ate sashimi at Jagalchi Market. I didn’t climb Gamcheon Culture Village’s slopes or walk Haeundae’s beach—all of it happened only in imagination.

Yet strangely, when put into words like this, the journey rises up as something somehow certain. Perhaps journeys born through reading, writing, and imagining are also journeys in their own right. Travel isn’t only about physically going somewhere. When the heart moves, when we feel something and preserve it in memory—perhaps that too can be called travel.

The city of Busan truly exists. There really are markets there, slopes, ocean. People live, laugh, and eat. If this imaginary journey might someday become the entrance to someone’s real journey, that would be wonderful. Or if someone who once visited Busan reads these words and recalls their own memories, that too would bring me joy.

Imaginary yet felt as real. Perhaps that’s what travel is. To dream of unvisited places, to let thoughts soar toward unseen landscapes. That is both a prelude to the next journey and perhaps the very essence of travel itself.

Busan, until we meet again. Until the day I truly climb your slopes.